Rise And Fall of Assyrian Empire

The Ethnic Origins of the Assyrians

Theories About the Origins of Semitic Peoples

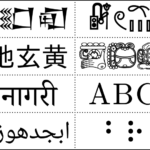

The Assyrians were a people who spoke a language from the Semitic language family. This group includes Arabic, Hebrew, Aramaic, Akkadian (and its dialects Babylonian and Assyrian), and Phoenician. There are two main theories about where the Semitic peoples originally came from:

- Arabian Peninsula Theory

According to this view, Semitic people started in the northern Arabian Peninsula during the Neolithic period. Because of climate changes like drought and population pressure, they began moving north. Over time, they spread into Mesopotamia, Syria, the Levant, and even North Africa. This theory suggests the main homeland of Semitic languages was in or near the Arabian Desert. - Levant Origin Theory

Another theory says that Semitic languages first developed in the Levant (modern Syria, Lebanon, Israel, and Palestine). From there, the people spread into Mesopotamia and Arabia. This theory is supported by how closely northern Semitic languages like Akkadian and Assyrian are linked with early Mesopotamian culture.

Both theories may be partly true. The migration of Semitic peoples was a long and complex process over thousands of years. The Assyrians were one group that formed as part of these migrations.

The ancestors of the Assyrians likely arrived in northern Mesopotamia, near the Tigris River, around 3000 BCE or earlier. This area had rich soil, water, and important trade routes, which helped the newcomers settle and start farming.

In this region, they met earlier local peoples such as:

- Hurrians: Non-Semitic, probably from the Caucasus. They lived mostly in eastern Anatolia and northern Mesopotamia.

- Subartu: An ancient people of northern Mesopotamia. Old Sumerian and Akkadian texts sometimes use “Subartu” to mean the land that became Assyria.

- Lullubi and Guti: Mountain peoples living in the Zagros Mountains. The Assyrians had both conflicts and cultural exchange with them.

The Formation of Early Assyria

The Reign of King Ilī-šuma

Ilī-šuma was an Assyrian king who likely ruled around the late 21st or early 20th century BCE. During his reign, Assyria was not yet a full empire but still organized as a city-state. Kings of this early period used the title iššiakum, meaning “representative of the god.” Ilī-šuma is known by this title.

Although his name appears in the Assyrian king lists, we also know him through inscriptions. These texts usually focus on topics such as temple construction, trade freedom, and loyalty to the god Ashur.

One of Ilī-šuma’s most famous acts was granting trade freedom to southern Mesopotamian cities. In one inscription, he declares:

“I, Ilī-šuma, granted tax and toll exemptions to the people of Sippar, Nippur, Ur, Uruk, and Eridu.”

This statement is remarkable. Even though Assyria was located in the north, Ilī-šuma made economic agreements with major cities of the Sumer-Akkadian south. He offered them tax reductions, which was both a commercial and diplomatic strategy.

His likely goals were:

- To secure Assyria’s trade routes,

- To attract southern merchants to northern markets,

- To turn Assur into a trade hub.

Thanks to these policies, Assur began to grow into an economic center before it became a military power.

During Ilī-šuma’s reign, religious buildings also gained importance. Temples built in the name of the god Ashur were a sign of the king’s devotion and legitimacy. One inscription says that Ilī-šuma built a large temple and ziggurat in the city of Ashur. These projects weren’t just religious acts — they also served to organize labor, boost local production, and strengthen the city’s structure.

First Contacts with Anatolia

Boğazköy, ancient Hattusa, was the capital of the Hittites. Excavations there uncovered many cuneiform tablets. Most of them were written in Hittite, but some are in Akkadian — showing cultural and diplomatic contact with Assyria.

In the 20th century BCE, Assyria created an organized trade network in Anatolia. The centers of this system were called karum (trade colonies). The most important one was Kültepe (Kaniš), though larger cities like Hattusa were also indirectly involved.

The number of karum-related tablets in Boğazköy is limited. However, Akkadian diplomatic texts and trade letters found there prove that Assyrian merchants from Kültepe had contact with Hittite elites, either directly or indirectly.

Examples of such documents include:

- Standard trade contracts

- Letters written in Akkadian

- Records about taxes, debts, and payments

These documents show that elite families in Hattusa were involved in trade with Assyrians, especially before the Hittite Kingdom was officially formed (during the time of the Hatti lords).

The tablets from Boğazköy also show that the Hittites learned cuneiform writing and archiving practices from the Assyrians. The Old Assyrian cuneiform script used in Kültepe later became part of Hittite diplomatic tradition. This means the relationship between the two civilizations was not only economic but also cultural.

From the Assyrians, the Hittites learned:

- Writing systems

- How to organize trade records

- Archival methods

The archives in Boğazköy reflect clear signs of Assyrian influence.

Thanks to the tablets found in Kültepe and surrounding areas, we know that Assyrian merchants brought the following to Anatolia:

- Tin (for bronze-making), brought from Mesopotamia and sold at high profit

- Woolen textiles

- Jewelry and precious metals

In return, they bought:

- Gold and silver

- Copper

- Local products

Although Boğazköy was not a main trade center like Kültepe, it still shows traces of Assyrian trade activity, especially during the Hittite Kingdom, when the central government kept close control over trade and record-keeping.

The Assyrian Empire and the Hurrian Domination

After the Hittites destroyed Babylon around 1594 BCE, new peoples became powerful in Mesopotamia. The Kassites took control in Babylon and formed a new system there. The Hittites united many kingdoms in Anatolia and expanded their influence as far as western Anatolia and the Aegean islands. The Hurrians, on the other hand, established the Mitanni Kingdom, which stretched from the Zagros Mountains to the Mediterranean Sea.

During this time, many powers were fighting to take control of raw materials in Anatolia, Syria, and Lebanon, and to gain access to Mediterranean ports for sea trade. These fights mostly benefited priests, royal families, and rich families. At the same time, local people under foreign control began to resist. Poor people and slaves also joined the fight against oppression. These struggles often caused major changes in the region’s political map.

Each new invasion created new problems. New rulers did not bring peace or wealth to the people. Instead, they spent money on building temples and on luxury for the ruling class, not on helping ordinary people.

After the rule of Shamshi-Adad and his sons, Assyria lost power. When the Assyrian trade centers in Anatolia disappeared, Assyria fell under the control of the Mitanni Kingdom. The few documents from this time show that Assyrian kings called themselves iššiakum, which means “high priest” or “religious servant of the god Ashur.” This shows that they had little political power.

However, the control of the Mitanni was not always strong. In the early 14th century BCE, Assyrian king Puzur-Ashur III made a treaty with Burnaburiash, a Babylonian king from the Kassite dynasty, about their shared border. Another Kassite king, Karaindaš, promised to respect the border. These events show that the Mitanni control sometimes weakened, and Assyria could still sign international treaties.

Still, the Mitanni Kingdom was the strongest power in the region, and the Assyrian kings were like governors under their rule. Many other small kingdoms were also ruled by Hurrian governors or lords loyal to the Mitanni. These local rulers often ruled harshly. One example is Arrapha (modern-day Kirkuk), located between Assyria and Babylonia, south of the Great Zab River.

Excavations in Arrapha found over 15,000 clay tablets written in Akkadian. These documents were part of the private archive of a rich Hurrian family, who had collected records for generations. The documents show that Arrapha was the center of a region that included several smaller kingdoms. Local lords and nobles were Hurrian, loyal to the Mitanni king, while the general population was Semitic and had no power in government.

The documents also show that Hurrian nobles were buying large amounts of land and expanding their farms. Local people became poorer and had to work as laborers for Hurrian landlords. When there were land disputes, the Hurrian nobles always won and became even richer.

We also learn that the Hurrian lords had good relations with Babylon. They sent gifts to the Babylonian king and continued trade between the regions.

Ashur-uballit and the End of Hurrian Rule

In the 14th century BCE, a very important change happened in Assyrian history. Until this time, Assyria was a small city-state in northern Mesopotamia. It was often controlled or influenced by stronger powers. In the 15th–14th centuries BCE, most of northern Mesopotamia and eastern Anatolia was under the control of the Hurrian Mitanni Kingdom. Mitanni had a strong army and ruled many small kingdoms. Assyria was also under Mitanni control and did not have full political independence.

This situation changed when Ashur-uballit I became king (around 1353–1318 BCE). He was different from earlier rulers. Instead of keeping the same system, he wanted to make Assyria powerful. He used the fact that the Mitanni Kingdom was getting weaker due to internal problems and attacks from the Hittites. Ashur-uballit took this chance to declare Assyria independent and began military and diplomatic actions.

Assyria’s rise was not only due to war, but also smart diplomacy. Ashur-uballit made contact with Egypt, one of the most powerful empires of the time. In the Amarna Letters, we see that he exchanged letters with Pharaoh Amenhotep IV (Akhenaten). These letters show that Assyria was now seen as an equal kingdom in international politics. The gifts and messages sent to Egypt were proof that Assyria no longer wanted to be seen as a small or weak state.

Inside Assyria, changes were also happening. Ashur-uballit strengthened the administration and increased royal power. In the city of Ashur, new buildings and temples were built. Temples dedicated to the god Ashur helped show the king’s religious authority. Ashur-uballit also formed a family alliance with Babylonia by marrying his daughter to the Babylonian king. This helped Assyria become more influential in southern Mesopotamia.

With Ashur-uballit’s rise, Mitanni rule over Assyria ended. After this, Assyria became a truly independent kingdom with its own army, political goals, and diplomatic power. Ashur-uballit’s actions opened the path for Assyria to later become a great empire. He is remembered as the king who gave Assyria its first real power.

The Age of Expansionist Kings

Starting in the 13th century BCE, Assyria began a new phase. The kings no longer focused only on defense. Now, they followed a policy of expansion, trying to control distant lands through wars and campaigns. This new strategy started with Adad-nirari I and became the main policy for future Assyrian rulers.

One important king of this period was Shalmaneser I (1274–1245 BCE), the grandson of Adad-nirari I. He destroyed what was left of the Mitanni Kingdom and expanded Assyria into Upper Mesopotamia, eastern Anatolia, and northern Syria. His campaigns into the Urartu region were the first steps in Assyria’s move north. Shalmaneser built fortresses, rebuilt cities, and forced local people to pay taxes. He also used mass deportation — moving large groups of people — to control the population and provide workers for Assyrian cities.

After him came Tukulti-Ninurta I (1244–1207 BCE), who took Assyria’s expansion to the next level. He became the first Assyrian king to conquer Babylon and briefly ruled there. This was more than just a military victory; it showed that Assyria was now stronger than Babylonia. But when he entered Babylon’s holy places and took the statue of the god Marduk to Ashur, it caused great anger. Many people saw it as a religious insult, and even Assyrian nobles were unhappy.

Tukulti-Ninurta didn’t just expand through war. He also showed his power through writing and architecture. He built a new capital called Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta, which was designed to reflect his authority and the will of the god Ashur. His inscriptions described not only victories but also the movement of people, the collection of taxes, and the rebuilding of cities. This shows that expansion was not just military, but also economic and administrative.

However, Assyria’s aggressive expansion also caused problems. Near the end of his rule, Tukulti-Ninurta faced rebellions. His actions in Babylon and growing discontent among the Assyrian elite led to his removal from power. This was the first time internal rebellion seriously challenged the king. Even so, the system he built remained strong, and expansion continued under future kings.

Assyria’s campaigns were not just about power. They also aimed to control trade routes, gain resources, and spread the will of the god Ashur. Assyrian kings believed their wars were religious duties — a way to defeat the enemies of their god. This idea became the ideological base for later Assyrian emperors.

Adad-Nirari I

Adad-Nirari I became king around 1307 BCE and ruled until about 1275 BCE. He was a very important figure in Assyrian history. Before his rule, Assyria was still small and not a strong empire. His grandfather, Ashur-uballit I, had started to make Assyria independent. Adad-Nirari continued this work and made Assyria stronger.

At that time, the Mitanni Kingdom was still active, but it was getting weaker. There were civil wars and outside pressures, especially from the Hittites. Adad-Nirari used this chance to attack Mitanni and expand Assyria to the west. He captured many important cities such as Taide, Apku, Irridu, and Washshukkanni, the heart of Mitanni. This ended Hurrian power in northern Mesopotamia.

He didn’t just conquer land — he also organized it. He added the new cities to the Assyrian system, set up governors, and built temples and military stations. This helped bring these areas fully under Assyrian control. Religion and politics were used together to make the king’s power stronger.

Adad-Nirari also expanded into northern Syria and eastern Anatolia. Some local tribes accepted Assyrian rule and paid taxes, while others were conquered. This showed that Assyria was now a power that ruled different people in many areas.

Internationally, Assyria became more important. Although he did not fight the Hittites directly, Adad-Nirari expanded into areas near them. He also fought with Babylonia over borders and won control of some land. From this time on, Assyria and Babylonia would become long-term rivals.

Adad-Nirari changed how the king was seen. In his writings, he called himself “the conqueror who fulfills the will of the god Ashur.” This kind of language became common in later Assyrian kings’ writings. It showed that the king’s power was not only political but also given by the gods.

In conclusion, Adad-Nirari I helped transform Assyria from a small city-state into a regional kingdom with military and political goals. He ended Mitanni control, expanded the kingdom, and laid the foundation for the future Assyrian Empire. He is remembered as one of the first real imperial kings in Assyrian history.

Shalmaneser I

Shalmaneser I ruled from around 1274 to 1245 BCE. He was the son of Adad-Nirari I and one of the most important kings of the Middle Assyrian Period. Shalmaneser did not only protect the kingdom; he worked to expand and organize it even more.

His first goal was to destroy what remained of the Mitanni Kingdom. Some Mitanni cities were still resisting. Shalmaneser led a big campaign to the Upper Habur River area and captured cities like Taide, Irridu, and Washshukkanni, the old Mitanni capital. This was a big military and symbolic victory — Mitanni was now gone, and Assyria became the strongest power in northern Mesopotamia.

But Shalmaneser didn’t stop there. He moved into Anatolia and northern Syria. In the mountains of eastern Anatolia, he fought local tribes and forced them to pay taxes or become part of Assyria. He also moved people from these regions to Assyrian cities — a policy known as forced resettlement. This helped reduce rebellion and increased the workforce in Assyria. This method would later become a regular part of the Assyrian Empire’s strategy.

He also improved administration in the new lands. He set up governors, built roads, and rebuilt cities. Some of these became military centers, others became places to spread Assyrian culture. City planning, writing, and record-keeping were all expanded in these areas.

Shalmaneser also built many religious buildings. He constructed temples and ziggurats, especially in the city of Ashur. He said he was doing the work of the god Ashur and that his victories were thanks to divine support. This helped make his rule seem holy and gave him more legitimacy.

Another key part of his reign was the growth of written records. Inscriptions from his time tell us not only about wars, but also about laws, city building, population movements, and administration. This shows that Assyria was not just a military state — it was becoming a complex, well-organized government.

In summary, Shalmaneser I expanded Assyria more than ever before and set up systems to keep control of the new lands. He created a model of how future kings would rule. His time was not just about war, but about creating a true imperial system with culture, religion, and administration.

Tukulti-Ninurta I Period

Tukulti-Ninurta I (around 1244–1207 BCE) was one of the most powerful and ambitious kings in Assyrian history. He inherited a strong empire from his father Shalmaneser I, but he did more than just keep it going — he expanded Assyria’s power across all of Mesopotamia and beyond. His rule was a time when Assyria reached the height of its military strength and when the king’s power became more centralized and sacred.

His most famous achievement was the conquest of Babylon. Assyria and Babylon had been rivals for a long time. During his reign, Tukulti-Ninurta defeated Babylon’s king Kashtiliash IV and took control of the city. Babylon was not just any city — it was the religious and cultural heart of Mesopotamia. By capturing it, Tukulti-Ninurta sent a strong political and symbolic message. He even took the statue of Babylon’s main god Marduk and brought it to Ashur, the Assyrian capital. This act showed power, but also caused a lot of anger.

Many people, especially in Babylon, saw this as a major disrespect to religion. Even in Assyria, some nobles and priests were upset. Taking Marduk’s statue disturbed the spiritual balance of the region. Although Tukulti-Ninurta wanted to show his strength, this act led to many problems, both inside and outside the kingdom.

As things got more difficult, he decided to build a new capital city called Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta near the Tigris River. This city had both political and religious importance. He built a great temple there for the god Ashur and used the new city to show his independence and divine authority. It was the first Assyrian capital built from scratch by a king, and it represented a new kind of royal power.

However, as his power grew, opposition increased. Nobles and priests were unhappy with his tight control and his actions against sacred traditions. Even his own sons joined a conspiracy against him. Eventually, he was overthrown and killed. This was the first time an Assyrian king was removed by an internal rebellion, marking a serious moment in Assyrian history.

After his death, there was a short period of political chaos in Assyria. Still, his work and reforms did not disappear. The cities he built and the lands he conquered remained part of Assyria. His idea that kings were not just rulers but also representatives of divine power shaped Assyrian thinking for centuries. His rule became a model for the future imperial system, especially in the Neo-Assyrian period.

In short, Tukulti-Ninurta I’s reign was both a time of great success and the beginning of internal crisis. He was the first Assyrian king to truly act like an emperor, but this also caused division. His rule shows how powerful and fragile the idea of empire could be.

Aššur-nadin-apli

Aššur-nadin-apli was the son of Tukulti-Ninurta I and ruled after his father was killed. His reign likely happened between 1207 and 1204 BCE. This was a troubled time in Assyrian history — the empire was weakened by internal conflict, but it did not collapse completely.

He came to power in a dramatic way. His father had taken Babylon and become very powerful. But many people in Assyria were angry at him for disrespecting Babylon’s religious places and for trying to change traditional rule. This anger led to a coup organized by his own sons, and one of them, Aššur-nadin-apli, became king afterward.

We don’t have many records from his reign. But we know that his time as king was focused more on defending the empire than expanding it. The glory days of big conquests were over, and Aššur-nadin-apli tried to keep the state stable during a time of tension and division. He likely had to deal with rebellions and lost some control over far regions.

Sources suggest that Assyria was less active in foreign wars during this time. Some lands that had been conquered earlier may have broken away. Aššur-nadin-apli probably tried to stop these problems, but his short rule did not allow much progress.

He also returned to a more traditional view of kingship. Unlike his father, who tried to show himself as a powerful, almost god-like emperor, Aššur-nadin-apli presented himself as a faithful servant of the god Ashur. This may have been an attempt to calm the anger of priests and nobles and to restore balance inside the kingdom.

Despite these efforts, his reign did not last long. After his death, Assyria once again fell into dynastic struggles and a period of weak kings. However, the disorder did not last forever. A few generations later, Tiglath-Pileser I would rise and restore Assyrian power.

So, Aššur-nadin-apli is remembered not for military victories but as a king who tried to repair the damage caused during his father’s rule. His short reign was a pause in Assyria’s imperial journey, but it helped keep the kingdom alive during a difficult time.

Period of Weakness

After the short reign of Aššur-nadin-apli, Assyria entered a period of weakness and instability. This lasted for about a hundred years, from the early to mid-12th century BCE. During this time, Assyrian kings could not achieve major victories like Tukulti-Ninurta I, and they also failed to fully restore order inside the kingdom. Some of the lands gained earlier were lost, and the central government often became weak.

One main reason for this weakness was internal political instability. After Tukulti-Ninurta I died, his sons fought over the throne. The royal office became a tool of power struggles instead of a respected religious role. Conflicts between priests, royal officials, and military leaders made it difficult to maintain order, especially in the capital city Aššur.

Another reason was the rise of external threats. The whole region of Mesopotamia was unstable. In Babylonia, the Kassite dynasty was also weakening. To the south, the Elamites launched attacks, while in the east, tribes from the Zagros Mountains caused trouble. In the west, Aramean tribes crossed the Euphrates and invaded Assyrian lands. The Assyrian army had a hard time dealing with all these threats and could not go on big campaigns because of problems at home.

Also, some provinces and border areas started to act independently. Local rulers refused to send taxes, built their own armies, and sometimes rebelled. This broke down Assyria’s normal system of central control. In some places, Assyria lost power completely. In others, its rule was only symbolic.

Economically, this was a hard time. Wars and internal conflict damaged farming and trade. Travel became dangerous. Production went down. Many farmers were taken to serve in the army or work as laborers, which weakened the local economy. Forced migrations and settlement programs could no longer continue like before.

Some kings of this time (like Enlil-kudurri-usur and Ninurta-apil-Ekur) are barely known. This is because few records were left, and these kings likely did not achieve much. The lack of royal inscriptions shows that the state ideology and the king’s ability to present his power were both weakening.

Despite all this, Assyria did not collapse. The central region around Aššur survived. Religious rituals continued, and the royal traditions stayed alive. This helped Assyria keep a base for future recovery. Later, a strong king would rise and bring back Assyria’s strength and expansion.

Restoration and the Reign of Tiglath-Pileser I

Tiglath-Pileser I (around 1114–1076 BCE) was a key figure in Assyrian history. After many years of weakness and disorder, his rise to power marked the beginning of a new era. He was not only a strong military leader but also a smart ruler and a builder of royal ideology. Under his rule, Assyria rose again.

One of his first and most important actions was to reorganize the military. During the weak period, the army had lost discipline and structure. Tiglath rebuilt the army, created new units, improved leadership, and led campaigns to give his soldiers real experience. Thanks to these reforms, Assyria was once again able to follow an expansionist policy.

His early campaigns went to the north and west. He marched into eastern Anatolia and made the Urartu tribes pay tribute. He captured many strongholds. In these areas, he not only fought battles but also collected tribute and left royal inscriptions to show Assyrian control. Campaigns against groups like Musasir, the Nairi lands, and the Subartu tribes helped restore fear and respect for Assyria.

In the west, Tiglath-Pileser crossed the Euphrates River and moved deep into Syria. Cities like Carchemish came under Assyrian influence. In some places, he used diplomacy; in others, he used force. These campaigns were early examples of the “power and diplomacy balance” that would become common in the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

Tiglath-Pileser didn’t only want land — he also wanted fame and prestige. He made sure his victories were recorded in detail. His writings on temple walls in Aššur and Nineveh talked about his military successes and his relationship with the god Ashur. These records weren’t just historical — they were political propaganda to show the king’s greatness.

His reign also brought a cultural revival. He supported education, writing, and archiving. In Aššur, written records were organized again. Texts on history, law, and prophecy were copied. This helped rebuild the memory and identity of the Assyrian state.

Tiglath-Pileser’s writing style was also different. He described himself in epic terms, as a mighty hero and tool of the god Ashur. He called his enemies “the wretched ones crushed by the wrath of the god.” This dramatic language became a model for later Assyrian kings.

But his reign was not without problems. In his later years, there were rebellions in some frontier areas. Aramean tribes became a serious threat in the west. They attacked cities and cut trade routes. Though Tiglath-Pileser pushed them back, the problem returned in the time of his successors.

Still, his reign is seen as a time when Assyria recovered its power, image, and culture. It is the second peak of the Middle Assyrian period. Tiglath-Pileser left behind a strong base that made the rise of the Neo-Assyrian Empire possible in later centuries.

After his death, his son Ashur-bel-kala and others took the throne. But none of them could fully keep Tiglath-Pileser’s strength. By the mid-11th century BCE, Assyria entered another quiet period. It was not a total collapse, but the energy of expansion was lost. The kingdom became more defensive and inward-focused.

The main threat during this time was again the Arameans, who crossed into Mesopotamia and took over some areas. They looted cities, blocked trade, and made it hard to keep control. The Assyrian army had limited success against them.

At the same time, relations with Babylon got worse. The Kassite dynasty had fallen, and new rulers came in. There were border fights and diplomatic tensions. Neither Assyria nor Babylon was strong enough to dominate the other. It was a time of uncertainty and balance.

Inside the kingdom, rulers tried to keep control. Temples and palaces were repaired, religious rituals continued, and basic administration was maintained. But no big new projects or ideas came from this period. The focus was on survival, not growth.

Royal inscriptions became fewer and simpler. Kings no longer called themselves great conquerors. Instead, they said they were protectors of the god’s order. This showed that the royal image had weakened.

Yet, Assyria did not fall apart. The system, traditions, and army stayed alive. This allowed the empire to survive and prepare for its next rise — the beginning of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. Even though this time looked quiet, the foundations of the future were still strong.

Neo-Assyrian Empire Period

The Neo-Assyrian Empire lasted from around 911 to 609 BCE and was the third and most powerful phase in Assyrian history. This was a time when Assyria turned its earlier successes into a fully organized empire, expanded its borders widely, and created a centralized government model for the first time in history. Its power was not just based on land but also on deep administrative, military, ideological, and cultural systems.

The empire began with Adad-Nirari II (911–891 BCE). Under his rule, Assyria began regular military campaigns again, especially against Babylon and Aramean regions. Later kings like Tukulti-Ninurta II and Ashurnasirpal II continued to rebuild the military and made forced migration policies a key part of the empire. By moving people from conquered lands to Assyrian cities, they reduced rebellion and increased labor forces. This helped build a multi-ethnic empire ruled from one center.

One of the key features of this empire was direct control. In earlier times, local rulers had more freedom. Now, governors were chosen by the king and were required to use the Assyrian language, laws, and religion. These governors sent reports, collected taxes, and provided soldiers. This was the first advanced government system in the ancient Near East.

Ideologically, Neo-Assyrian kings saw themselves as more than rulers — they were protectors of the world order and destroyers of enemies. In royal writings, kings like Ashurnasirpal II, Tiglath-Pileser III, Sargon II, and Sennacherib describe their victories in very dramatic ways. Enemies are shown as being torn apart or blinded. This wasn’t just storytelling — it was a way to create fear and respect among the people.

This period also saw a major boom in architecture and culture. Capital cities like Kalhu (Nimrud), Dur-Sharrukin (Khorsabad), and Nineveh were built or expanded. These cities had huge palaces, temples, ziggurats, statues, and wall carvings. These places were not just political centers — they were symbols of Assyrian power and culture. The carvings on palace walls showed the king’s battles and his connection with the gods.

Militarily, Neo-Assyria had the most advanced army of its time. It had not only chariots and foot soldiers, but also siege machines, engineers, and spies. The army was professional, well-organized, and campaigns were planned yearly.

In short, the Neo-Assyrian Empire was one of the most developed systems of the ancient world — in government, military, and culture. It kept control for nearly three centuries and was a source of fear and power. But because it was built on constant expansion and force, it eventually started to collapse from within.

Adad-Nirari II (911–891 BCE)

Adad-Nirari II is seen as the first great king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. His rise to power ended a long period of weakness and defense. With him, Assyria became strong and active again, with regular campaigns and a clear imperial ideology.

His first task was to restore order inside the kingdom. He removed untrustworthy governors and replaced them with loyal officials. He rebuilt the city of Ashur, restored temples, and reorganized the army. These changes prepared Assyria for future campaigns.

His first major campaigns were against Babylon. He defeated King Shamash-mudammiq, secured the southern borders, and added border cities to Assyria. Later, he also beat another Babylonian king, Nabu-shuma-ukin I. These victories gave Assyria not only land but also ideological power.

Then he turned north and east. He attacked mountain tribes like the Lullubi and made them pay tribute. His campaigns reached into Urartu and eastern Anatolia. He also moved people from these areas into Assyria — reducing rebellion and adding to the population.

Another important contribution of Adad-Nirari II was building a tax and record system. Tribute and taxes from new lands were sent to Ashur. This became the base of Assyria’s economy and was improved by later kings.

In his writings, he called himself “faithful servant of Ashur” and “destroyer of enemies.” He described his victories in detail but also showed himself as a protector of the people. This dual image — both warrior and builder — became a model for future Assyrian kings.

Ashurnasirpal II (883–859 BCE)

Ashurnasirpal II, son of Tukulti-Ninurta II, turned Assyria into a multi-ethnic superpower through fear and power. Under him, Assyria expanded not just militarily, but also in government, city-building, and art. He was a great general and also a master of propaganda.

When he became king, he first crushed rebellions and defeated northern tribes like the Lullubi, Nairi, and Subartu. He didn’t only beat them — he destroyed villages, forced people to move, and used extreme punishments. In his inscriptions, he says:

“I flayed their skins alive, impaled them, and hung them on walls.”

This shows how Assyria used fear as a tool of empire.

In the west, he reached deep into Syria. He dealt with Aramean city-states and Phoenician trade cities through both war and diplomacy. Important cities like Carchemish, Hama, and Arpad submitted and paid tribute. This marked the first direct contact between Assyria and the Mediterranean.

One of his biggest projects was rebuilding the city of Kalhu (Nimrud). He made it the new capital, full of huge palaces, temples, and ziggurats. The most famous building was the Northwest Palace, decorated with amazing wall carvings. These reliefs showed the king with gods, in battles, or during rituals. They were not just beautiful art — they sent strong political messages: the king was chosen by the gods and crushed his enemies.

During his time, Assyrian writing and record-keeping also improved. Campaigns, building projects, and administrative acts were all written down and stored in temples and palaces. His period saw the rise of a new royal writing style that was elegant and formal. This style influenced later kings like Sargon II, Sennacherib, and Ashurbanipal.

Forced Relocations and the Legacy of Ashurnasirpal II

One of the key parts of Ashurnasirpal II’s imperial strategy was the use of forced relocations. People from conquered lands were moved to cities like Kalhu and other Assyrian centers. This gave the empire new workers and broke up potential groups of rebellion. Later kings adopted this method, and it became a system of population control across the empire.

Despite all his military success, Ashurnasirpal II couldn’t turn constant war into lasting peace. His rule was based on fear and domination, and many areas that paid tribute rebelled after his death. Still, his cultural, political, and ideological legacy became the foundation of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, giving a strong base for his son, Shalmaneser III.

Shalmaneser III (859–824 BCE), the son of Ashurnasirpal II, expanded his father’s system even further. He led military campaigns almost every year. His most famous battle was the Battle of Qarqar (853 BCE), where he fought against a large alliance of Syrian and Levantine states, including King Ahab of Israel. The battle was not a total victory, but it symbolized Assyria’s move toward the Mediterranean.

Shalmaneser expanded Assyrian rule to Elam in the east and Syria and Cilicia in the west. But in the final years of his long reign, internal problems began to rise, including a prince-led rebellion. This weakened the royal court and caused temporary instability.

Tiglath-Pileser III: The Second Founder

After a time of civil conflict, Tiglath-Pileser III (reigned from 744 BCE) came to the throne and restructured the empire. He is often called the second founder of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. He increased central control, replacing local kings with Assyrian governors. This made Assyria a truly centralized empire.

He also expanded the use of mass deportations — moving large groups of people after every conquest. Tiglath-Pileser III extended Assyrian power into Palestine, Lebanon, and northern Arabia, reaching the Mediterranean and beyond. His system was so effective that later kings followed his model almost exactly.

Sargon II and the Peak of Power

Sargon II (722–705 BCE) was both a warrior and a builder. In 722 BCE, he destroyed the Kingdom of Israel and exiled its people — one of the harshest examples of Assyrian deportation policy. He also attacked Urartu and Elam, and reached as far as Cyprus and Egypt.

Sargon founded a new capital city, Dur-Sharrukin, to symbolize his power. But he died suddenly in battle, causing instability at the court.

His son, Sennacherib (705–681 BCE), is known for his siege of Jerusalem and the destruction of Babylon in 689 BCE. Babylon was seen as a sacred city, so destroying it caused major religious and political backlash. Many believe this act led to his own assassination by his sons.

Still, Sennacherib built Nineveh into a grand capital, with canals, palaces, and stone reliefs showing Assyrian power at its height.

His son Esarhaddon (681–669 BCE) rebuilt Babylon, trying to restore peace and religious balance. He also invaded Egypt, briefly making it part of the empire. Assyrian governors were placed in Egyptian cities — a high point of Assyrian global influence.

Under Ashurbanipal (669–627 BCE), Assyria became not only a military power but also a center of learning. He built the Royal Library of Nineveh, which preserved many texts, including the Epic of Gilgamesh.

Ashurbanipal destroyed Elam, removing one of Assyria’s rivals. But in his later years, civil unrest, court politics, and an overstretched empire began to weaken the state.

Collapse of the Neo-Assyrian Empire

After Ashurbanipal’s death (after 627 BCE), Assyria entered a time of chaos and collapse. We don’t know clearly who ruled — tablets mention kings like Ashur-etil-ilani and Sin-shar-ishkun, but their reigns are poorly documented. What is clear is that central control broke down and the empire fell apart rapidly.

Two new powers rose against Assyria: the Medes (from Iran) and the Neo-Babylonian Empire. Starting in the 620s BCE, they began a full-scale attack on Assyria. In 612 BCE, their combined forces destroyed Nineveh after a long siege. Temples and palaces were burned, and the royal family was killed or fled. This was not just the fall of a city — it was the end of an entire civilization.

Some Assyrian nobles and soldiers regrouped in Harran, trying to rebuild the kingdom. A king named Ashur-uballit II led the last defense with help from Egypt. But in 609 BCE, Harran also fell, and Assyria was gone as a political power.

The End of an Era

Assyria’s fall was more than physical. Its religion, language, and government all disappeared. The new powers — Babylon and the Medes — did not continue Assyrian traditions. The Assyrian language (a dialect of Akkadian) died out within a few decades.

The collapse was total, unusual for the ancient world.

But Assyria’s legacy lived on. Its military strategies, government systems, legal ideas, and royal ideology influenced later empires — from the Persians to the Romans. Though the empire vanished, its impact on history remained strong.

![Coin of Arsaces I. The reverse shows a seated archer carrying a bow, with the Greek legend reading "ΑΡΣΑΚΟΥ" (right) and "[AYT]OKPATOP[OΣ]" (left), meaning [coin of] "Arsaces"](https://historifyproduction.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/500px-Coin_of_Arsaces_I_1_Nisa-1-150x150.png)