The Historical Significance of the Invention of Writing

The invention of writing stands as one of the defining milestones in human history. It marked the transition from prehistory (reliant on oral tradition) to recorded history, allowing knowledge and ideas to be preserved across generations. The earliest known example of this transformative technology emerged in ancient Mesopotamia around 3200 BC, when the Sumerians developed the first writing system. This breakthrough is widely regarded as the most significant cultural contribution of the Sumerian civilization. By replacing oral tradition with written records, the invention of writing enabled civilizations to store and share knowledge on an unprecedented scale.

Civilization at the Dawn of the Invention of Writing

Who were the people responsible for this momentous invention of writing? They were the Sumerians, the inhabitants of Sumer in southern Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) during the 4th millennium BC. The Sumerians were pioneers of urban civilization: by around 3500–3000 BC they had established city-states such as Uruk, Ur, Eridu, and Lagash, complete with monumental temples (ziggurats), irrigation agriculture, and burgeoning trade networks. One of these, the city of Uruk, covered over 250 hectares and has been called the first true city in world history.

Uruk’s rapid growth was part of a wider population boom in Mesopotamia during the late 4th millennium BC. Scholars debate the causes, but the result was clear – large concentrations of people and wealth that demanded new forms of organization.

Crucially, Sumerian cities were organized around temple and palace institutions that managed vast agricultural estates. In Uruk, for example, the temples oversaw storage and redistribution of grain, beer, livestock, and other resources to support priests, craftsmen, and laborers. The need for accounting and the disbursement of rations from these temple economies provided the context for the invention of writing.

Simply put, as society became more complex, tallying goods in one’s memory (or with primitive tokens) was no longer sufficient. Sumerians faced practical challenges of record-keeping: how to track offerings to the gods, payments to workers, or trades with distant lands in a reliable, permanent way. Their resource-scarce environment also encouraged innovation – they had little stone or wood for making records, but they had an abundance of clay in the river valleys. As one historian notes, “they had few trees, almost no stone or metal,” so the Sumerians ingeniously used clay for everything from bricks to pottery to tablets for writing.

How the Sumerians Pioneered the Invention of Writing (Cuneiform)

The Sumerian invention of writing did not emerge fully formed overnight – it was the culmination of incremental steps in visual communication. By around 3400–3200 BCE, officials in Sumerian temples began using simple pictures etched into clay tablets to represent the goods and numbers they needed to track.

These early pictograms – called proto-cuneiform – were essentially abstract drawings of objects: a picture of a jar might stand for “beer,” or a stylized sheep’s head might mean “sheep.” The tablets were small clay squares or rectangles, impressed or inscribed while the clay was damp and then left to harden. Importantly, this method took advantage of the materials at hand: a reed stylus (pen) was pressed into the clay to draw the signs, which naturally produced wedge-shaped strokes. Over time, scribes found it more efficient to press the stylus into the clay rather than draw lines, and the pictorial signs became increasingly stylized and wedge-like, giving rise to the script known as cuneiform (from the Latin cuneus, meaning “wedge”).Why did the Sumerians invent this system? Initially, not for art or literature – it was devised “not for letters, literature or scripture, but for accountancy” as the British Museum observes.The very first texts are mundane accounting records. For example, one clay tablet from Uruk (c. 3100 BC) itemizes beer rations allotted to workers.It isn’t a story or a prayer; it’s essentially a receipt. On that tablet, numbers and symbols indicate how much beer was given out, using an early repertoire of signs: hundreds of different characters were invented to represent goods, animals, units of measure, and people’s names.This system of pictographs and numerical symbols was a huge improvement over prior recording methods (like counting tokens) because it allowed a permanent, detailed record to be kept. One no longer had to rely on memory or tokens in a clay envelope – the tablet itself recorded the transaction for anyone who could interpret the signs.

A Late Uruk-period clay tablet (c. 3100–3000 BC) recording beer rations for workers – one of the earliest known examples of writing. The wedge-marked symbols are derived from simplified pictures. For instance, the sign for “beer” is an upright jar with a pointed base (appearing three times), with wavy lines inside the jar to signify the beer itself. Another sign (a bowl tipped toward a human head, visible at lower left) means “to eat,” indicating this text is about food rations.Such tablets show that the invention of writing originally served economic and administrative needs, not storytelling or myth.

As the uses of writing expanded, so did the script itself. The Sumerians soon realized that drawing exact pictures had limitations – you could convey “two sheep temple Inanna” with pictographs (to record, say, two sheep delivered to the temple of the goddess Inanna) but you couldn’t easily express more abstract ideas or verb tenses. Over the course of the 3rd millennium BC, cuneiform writing grew more sophisticated. Scribes began combining signs and using them in new ways. They applied the “rebus principle,” where a picture could represent not just the object it depicted but also a similar-sounding word or syllable. For example, a pictograph of an arrow (Sumerian word ti) could also be used to represent the syllable ti in any word. In this way, signs came to represent sounds (phonograms) and not just things. By around 2600 BC, the system had evolved into a true writing system capable of recording spoken language fully.

A scholar notes that from this point, cuneiform was a complex mix of word-signs and phonetic signs that allowed scribes “to express ideas” and record grammar.

In other words, writing had moved beyond mere lists of nouns – it could capture names, actions, and ideas, and thus anything people could say.

What started as crude scratches in clay had become a flexible instrument for communication. Different combinations of wedge-marks could spell out syllables, which in turn formed words. The Sumerian script now could record the full range of their language, including myths, prayers, laws, and letters. The invention of writing had truly arrived at a revolutionary point: it was no longer just a memory aid for accountants, but a vehicle for all manner of human thought.

Early Uses Following the Invention of Writing in Sumer

Once the Sumerians had this powerful new tool, what did they do with it? The early uses of writing in Sumer (and in Mesopotamia generally) covered virtually every aspect of life that required recording. By the middle of the 3rd millennium BC, cuneiform writing – still usually written on clay tablets – was used for a vast array of purposes: economic, religious, political, literary, and scholarly documents all appear in the archaeological record.

The Sumerians, it seems, were quick to apply writing wherever it could be useful. Key early uses of writing included:

Economic and Administrative Records: This was the original use of cuneiform and remained paramount. Tablets from temple and palace archives record inventories of goods, land transactions, tax assessments, and ration distributions. For example, tablets itemize shipments of grain or wool, lists of workers and their daily barley rations, and accounts of offerings made to the temple. Long-distance trade was also facilitated by writing: merchants could send records of contracts, debt notes, and inventories with caravans. Early cuneiform tablets often served as shipping manifests, noting the type and quantity of goods shipped, their value, and the parties involved. In these economic texts, there was no need for flowery language – just the facts and figures. This administrative use left thousands of clay tablets in sites like Uruk, Shuruppak, and Ebla, showing how indispensable writing became for running the complex Sumerian economy.

Religious and Ritual Texts: As writing became more prevalent, it was adopted by the religious sphere as well. Sumerian priests and scribes used writing to record temple donations and accounts, to catalogue offerings and ritual supplies, and to copy down the words of prayers, hymns, and incantations. Some of the earliest literature is in fact religious: for instance, the Temple Hymns (attributed to the priestess Enheduanna, 23rd century BC) are a collection of written hymns to Sumerian deities. Myths and epics with religious themes were also preserved in writing as the oral traditions were eventually copied onto tablets. By around 2500–2000 BC, we find myths like the tale of “Inanna’s Descent into the Underworld” and other creation stories written in cuneiform. These texts show that writing had entered the realm of spirituality and cosmology, allowing complex religious ideas to be recorded and transmitted.

Literature and Education: The invention of writing opened the door for literature in the form of epics, poems, proverbs, and stories. The Sumerians are credited with the earliest known literary compositions. Perhaps the most famous is the Epic of Gilgamesh, which began as a cycle of Sumerian poems about the hero-king Gilgamesh (c. 2100 BC) and was later woven into an Akkadian epic. Sumerian scribes also recorded fables, essays (like the “Instructions of Shuruppak,” a father’s advice to his son), and proverbs. Writing made it possible to preserve these works and to establish a scribal education system. Tablets from the Old Babylonian period (circa 1800 BC, but preserving earlier Sumerian material) reveal the existence of scribal schools where students copied out lists of words, signs, and proverbs as exercises. Literature and learning benefited immensely from writing – now knowledge could be compiled in libraries and passed down. The fact that cuneiform allowed the creation of literature is highlighted by scholars as one of its greatest achievements. The world’s first authored literature and the first libraries were born in Sumer due to the written word.

Legal and Political Documents: Another crucial use of writing was in the sphere of government and law. Rulers began to use writing to issue decrees and edicts, to administer their realms, and to proclaim their achievements. For example, King Entemena of Lagash (circa 2400 BC) left inscribed stone monuments detailing a treaty and border agreement – essentially an early diplomatic document set in stone. More famously, by around 2100 BC, the Sumerians had written down the first law codes. The Code of Ur-Nammu from that period is the oldest known law code in the world, laying out legal principles and penalties in the Sumerian language. (It predates the Babylonian Code of Hammurabi by several centuries.) Such texts show that law and justice were systematized through writing. Similarly, kings used writing to glorify their reigns: victory steles, royal inscriptions on temples, and year-name lists (recording notable events of each year) all relied on writing. In governing their city-states and later empires, Mesopotamian rulers found writing to be an indispensable tool for communication and control.

The Impact of the Invention of Writing on Sumerian Society and the Wider Ancient World

The invention of writing fundamentally transformed Sumerian society and rippled outward to affect many other cultures. In Sumer itself, writing had an immediate impact on social and political organization. It created a new elite profession: the scribes. Scribes were those trained to read and write cuneiform, and they became vital functionaries – working in temples, palace bureaucracies, and merchant offices. Scribes kept accounts, drafted letters and contracts, and copied literature and scientific texts. As a result, they were held in high esteem in the social hierarchy (in ancient lists of occupations, the scribe is often ranked near the top). The establishment of scribal schools during the Early Dynastic period institutionalized this, ensuring that a class of literate officials continued to thrive. The presence of writing thus contributed to a more stratified society where knowledge of cuneiform was power.

Writing also enabled the centralization and expansion of government. Administrators could coordinate large projects – like canal construction or temple building – by issuing written orders and keeping records of workers and supplies. Kings could send written commands to distant governors. As cities grew into larger states, this ability to manage information was crucial. Indeed, it’s noted that as the need for permanent accounting increased with the rapid growth of cities, writing “took off” and became ever more essential. We see this in the archaeological record: the number of tablets explodes at the end of the 4th millennium BC, reflecting a bureaucracy coming to depend on written documentation. In this way, the invention of writing underpinned the development of the first kingdoms and empires in Mesopotamia.

Beyond practical management, the cultural impact of writing was profound. Knowledge could be preserved and accumulated in a way never before possible. The Sumerians, once they had writing, “sought to record virtually all of the human experience”. They wrote about the deeds of kings and the will of the gods, about the movements of stars and the prices of barley. Over centuries, this created a corpus of Mesopotamian knowledge in astronomy, mathematics, medicine, and literature that could be built upon by subsequent generations. For example, by the late 2nd millennium BC, Babylonian scholars (heirs to the Sumerian tradition) had compiled astronomical observations and mathematical tables on clay tablets, enabling discoveries like the advanced Jupiter calculations mentioned earlier. None of that intellectual progress would have been possible without the foundation of writing to record data and hypotheses.

The invention of writing also had a unifying and spreading effect. Once invented in Sumer, writing did not stay confined to Sumer. It was eagerly adopted and adapted by neighboring peoples. The Akkadians, a Semitic people in Mesopotamia, learned cuneiform and by 2500 BC were using it to write their own Akkadian language. They modified some signs and added others, but essentially took up the Sumerian invention of writing for themselves. As Mesopotamia came under Akkadian, then Babylonian and Assyrian rule, cuneiform became a lingua franca of administration and scholarship. Over 3,000 years, the wedge-shaped script was used by many cultures and in multiple languages. Akkadian (Babylonian and Assyrian dialects) became the international language of diplomacy in the Late Bronze Age, written in cuneiform on clay tablets found from Egypt to Turkey. Other peoples – the Elamites in Iran, the Hittites in Anatolia, the Hurrians, and more – all used cuneiform script, testifying to how influential the Sumerian writing system was. One historian notes that the Sumerian invention “was borrowed by subsequent civilizations and used across the Middle East for 2,000 years”. This wide adoption greatly facilitated cultural exchange and record-keeping across a vast region of the ancient world.

In summary, the impact of the invention of writing on Sumerian society was transformative: it professionalized knowledge, strengthened the state, and enriched the culture. And on the wider ancient world, it set off a chain reaction – Sumer’s neighbors either adopted cuneiform or were inspired to create writing systems of their own (as we’ll see next). The ability to write down information changed what ancient societies could achieve. Large-scale economies, codified laws, canonical literature – all these hallmarks of civilization hinged on writing. It is telling that when modern scholars speak of “history” beginning, they often mean the start of written records in Sumer. The Sumerians’ tiny clay tablets ended up having an immeasurable effect on human development.

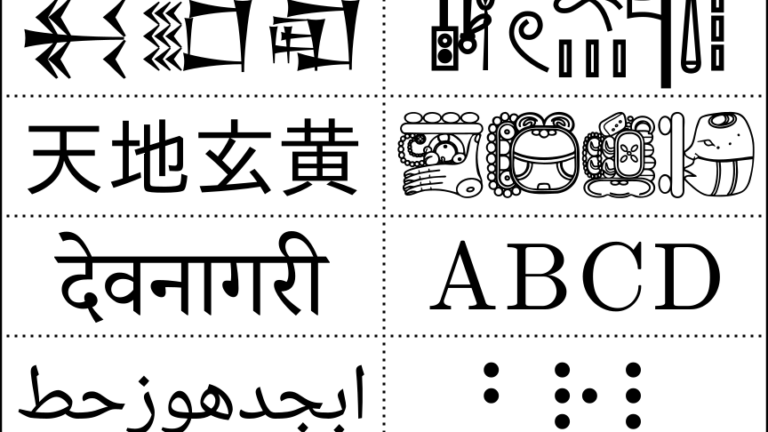

Comparing the Sumerian Invention of Writing with Other Early Writing Systems

The Sumerian invention of writing was not the only instance of writing emerging in antiquity. In fact, writing appears to have been invented independently in several places, roughly around the same era. Two other great early civilizations – ancient Egypt and the Indus Valley civilization – developed their own writing systems not long after (or possibly contemporaneous with) the Sumerians. Comparing these systems provides insight into how the concept of writing spread and diverged.

Egyptian Hieroglyphs: In Egypt, the hieroglyphic writing system was in use by *c.*3200–3100 BC, only a few centuries after the first Sumerian cuneiform. The earliest Egyptian hieroglyphs are found on artifacts from the late Predynastic period (Dynasty 0), such as inscribed ivory tags and pottery from Tomb U-j at Abydos. These earliest texts were likely labels for royal grave goods or notations of offerings, indicating that as in Sumer, the initial function of writing in Egypt was administrative/identificatory. Despite the close timing, scholars generally believe that Egyptian writing arose independently of Sumerian influence. There were certainly cultural contacts between late 4th-millennium Egypt and Mesopotamia – for instance, Egypt adopted Mesopotamian-style cylinder seals, and some early Egyptian art motifs (like the serekh palace facade design) show Mesopotamian inspiration. It has been hypothesized that the idea of writing might have been known to the Egyptians through trade contacts (i.e. they might have heard of Mesopotamian scribes keeping records). However, the Egyptian hieroglyphic script is distinct in form and underwent its own development. The hieroglyphs remained pictorial in appearance (little drawings of people, animals, and objects), whereas cuneiform became abstract wedges. Moreover, early hieroglyphs already included phonetic components – Egyptian scribes, like their Sumerian counterparts, figured out the rebus principle and created symbols for sounds (consonants) and used determinatives (marker signs to clarify meaning) alongside logograms. This means Egyptian writing, from its inception, had a complex system of unpronounced classifiers and phonetic signs that is quite different from the mainly syllabic cuneiform. In use, hieroglyphs were employed especially in royal and religious contexts: by 3000 BC, we see kings’ names and titles inscribed on stone (such as the famous Narmer Palette) and labels describing ritual events or offerings. Hieroglyphic writing was often more monumental – carved in stone on tombs and temple walls – whereas cuneiform was usually written on clay. Despite these differences, both systems share a common achievement: they show humanity figuring out how to represent language visually. Egypt’s invention of writing thus mirrors Mesopotamia’s in purpose (record-keeping and royal display) and timing, even if the two scripts look very different. Significantly, each appears to have been an independent invention of writing, demonstrating a parallel leap in cognitive and cultural development.

Indus Script: The Bronze Age civilization of the Indus Valley (in present-day Pakistan and northwest India) also developed a form of writing, though later and far less understood. The Indus script was in use during the Mature Harappan period, roughly 2600–1900 BC. During the earlier, formative period (c. 3500–2700 BC), we see only sporadic symbols (perhaps a precursor to writing) on pottery shards. But by the height of the Indus cities (Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, etc.), the people were engraving seals and tablets with a set of distinctive signs – this is considered the fully developed Indus writing system. However, the nature of this system remains a mystery because, unlike cuneiform and hieroglyphs, the Indus script has not been deciphered. Scholars have catalogued about 400 basic signs and many short inscriptions (mostly around 5 characters in length, the longest about 26), but we do not know what language it encodes. Without a bilingual “Rosetta Stone” or lengthy texts, determining how the Indus script worked (whether it was alphabetic, syllabic, or logographic) is extremely challenging. What we can say is that the Indus script appears to be an independent invention of writing by that civilization. It shares some superficial similarities with other scripts (for example, there are abstract geometric shapes, human and animal motifs), but it is unique to the Indus culture. The usage of the Indus script, as gleaned from context, seems to align with administrative and commercial needs: the script is most commonly found on stamp seals, which were likely used to mark goods and property, and on clay tags or tablets possibly attached to traded commodities. Tantalizingly, Indus seals have been discovered at Mesopotamian sites, indicating that Indus merchants traded with Mesopotamia and left their (undeciphered) inscriptions on goods that traveled west. This shows that by 2000 BC, the idea of writing had diffused enough that people in Mesopotamia were encountering a foreign script, even if they couldn’t read it. In terms of content, because the inscriptions are brief, it’s thought that the Indus script might have mainly conveyed owner names, titles, or religious symbols rather than long narratives. There is evidence some Indus signs were combined with pictorial motifs in what might be mythological scenes, hinting at a possible religious or ceremonial use as well. Unfortunately, until the script is deciphered (if ever), the full story of the Indus invention of writing remains elusive. What is clear is that the Indus Valley joined the club of early civilizations who invented writing from scratch, independently demonstrating that where complex society grew, so did the need for written communication.

Beyond Sumer, Egypt, and the Indus Valley, other regions would later develop writing independently as well – for example, the Chinese around 1200 BC (oracle bone inscriptions) and the Maya (and other Mesoamerican cultures) by around 500 BC. Each of these scripts has its own fascinating path. But the Sumerian, Egyptian, and Indus examples highlight that the invention of writing was a pivotal innovation that occurred in multiple cradles of civilization, each time with enormous consequences. In Sumer and Egypt, happily, we can actually read the texts and thus know their history; in the Indus case, the script’s secrets remain locked in those tiny seal carvings. Yet all three instances underscore the universal human impulse to record information – and the similar solutions societies hit upon (using signs for words and sounds) despite being worlds apart.

Influence on Later Writing Systems

The Sumerians’ invention of writing left a lasting legacy that long outlived the Sumerians themselves. The cuneiform script in particular had an extraordinarily long run and influenced many subsequent writing systems. As we noted, cuneiform was adopted by a succession of Mesopotamian cultures and modified to write languages in completely different families. This adaptability of cuneiform – a testament to the robustness of the Sumerian invention – meant that even as Sumerian as a spoken language died out (by around 2000 BC), the script continued to thrive. Scribes in the Akkadian, Babylonian, and Assyrian empires still used Sumerian cuneiform signs (with some tweaks) for their writing. In fact, Sumerian remained a classical language of learning in Mesopotamia (much like Latin in medieval Europe) for over a thousand years, with students copying Sumerian literary texts in cuneiform as part of their education.

Cuneiform’s influence also spread beyond Mesopotamia. The script inspired offshoots and analogous systems elsewhere. One notable example is the Ugaritic alphabet (c. 1400 BC) used in Syria: it was an alphabetic script (signs for individual consonant sounds) but written in the familiar wedge-shaped strokes on clay tablets, essentially merging the idea of an alphabet with cuneiform style. Another example is Old Persian cuneiform (circa 500 BC), devised under Darius the Great – it was a simplified quasi-alphabetic cuneiform used to inscribe Persian royal proclamations. These instances show how later peoples consciously built on the prestige and concept of cuneiform for their own purposes. More indirectly, one could argue that the very notion of writing down language in a systematic way – a notion pioneered in Sumer – paved the road for the development of the alphabetic scripts that would eventually replace cuneiform. By around 1000 BC, in the Levant, the Phoenicians created an alphabet (likely inspired by earlier Egyptian consonant signs), and this new streamlined writing system spread widely. In Mesopotamia itself, cuneiform tablets gradually gave way to alphabetic Aramaic script on parchment during the first millennium BC. Cuneiform was “abandoned in favor of alphabetic script” sometime after 100 BCE, after a lifespan of roughly 3,000 years. The last datable cuneiform texts (astronomical tablets in late Babylonian) come from the 1st century AD. Thereafter, knowledge of how to read the wedge-signs was lost.

Even after cuneiform fell out of use, its legacy persisted in the sense that Mesopotamia’s literary and legal heritage (recorded in cuneiform) continued to influence newer civilizations (for instance, elements of Mesopotamian mythology are echoed in the Hebrew Bible, and Greek scholars later documented some Mesopotamian knowledge). But a more direct legacy awaited the modern era. For almost two millennia, the hundreds of thousands of clay tablets left behind in the ruins of Mesopotamia lay buried and unread. No one in classical Greece or medieval times could read Sumerian or Akkadian cuneiform, so the very existence of the Sumerians was forgotten. It was only in the 19th century, with archaeological excavations and the efforts of decipherers, that cuneiform writing was finally cracked. In 1837 Henry Rawlinson famously copied and deciphered the trilingual Bisitun (Behistun) Inscription, using Old Persian, and scholars like Georg Grotefend and Edward Hincks helped unlock Akkadian and Sumerian after that. When at last the ancient clay tablets spoke again, our understanding of history was transformed. Suddenly, the Bible was no longer the oldest record of the past – we now had documents far older, from the pens of Sumerian scribes. The stories of the Flood and Creation had Mesopotamian versions in the Epic of Gilgamesh and other texts, revolutionizing biblical studies. Most importantly, an entire lost civilization – Sumer – emerged from oblivion, primarily thanks to its writings. As one historian noted, before cuneiform’s decipherment “nothing was known of the ancient Sumerian civilization”. Now, because those people invented writing long ago, they could at last tell us their name and their story. This is perhaps the greatest legacy of the Sumerian invention of writing: it allowed the thoughts of people 5,000 years ago to re-enter human knowledge today.

In terms of influence on later writing systems, we can conclude that while cuneiform itself did not directly morph into the scripts we use now (our alphabet comes more from the Phoenician/Greco-Roman lineage), the very concept of literate civilization owes a debt to Sumer. The idea that information can be fixed in physical form and transmitted across time is something every modern writing system inherited from these first inventions of writing. Cuneiform’s extensive use set a pattern that writing is an essential feature of a civilized state. It’s no accident that the word “cuneiform” itself became synonymous with ancient writing in general, or that so many later cultures kept using those wedge marks for centuries. Even as alphabets took over, the practice of keeping archives, writing correspondence, and composing literature continued – a continuous tradition that started at Sumer.

The Invention of Writing as a Cornerstone of Civilization

The story of the Sumerians and the invention of writing illustrates how a simple idea – pressing marks into clay – can alter the course of civilization. In Sumer, writing began as a practical tool to meet a concrete need, but it blossomed into an instrument for preserving memory, authority, and creativity. The ability to write replaced the limitations of oral tradition and enabled the storage and dissemination of knowledge across both time and space. Thanks to writing, the accumulated wisdom of one generation could be passed to the next with far less loss; rulers could govern larger realms with records and laws; and epics could outlive their authors. It is no exaggeration to call the invention of writing a cornerstone of civilization – without it, complex urban societies as we know them would have been impossible.

The Sumerians, by inventing cuneiform writing, unlocked humanity’s “collective memory.” They turned spoken words and ideas into lasting records, ensuring that history itself could be recorded. This breakthrough did not remain isolated: it sparked or inspired other writing systems around the world, each supporting its own civilization’s growth. From the banks of the Euphrates to the Nile, Indus, and beyond, writing became the engine driving administration, science, literature, and cultural continuity. And in a poignant full-circle, the clay tablets that Sumerian scribes filled so long ago ended up preserving their civilization’s legacy until modern scholars could read them again – allowing the voices of ancient Mesopotamia to speak to us today. In sum, the invention of writing by the Sumerians stands as one of humanity’s greatest innovations, truly a foundation for all the achievements of recorded history and a testament to the ingenuity of our earliest civilizations.

Sources:

-

British Museum – The first writing: counting beer for the workers (Google Arts & Culture)artsandculture.google.comartsandculture.google.comartsandculture.google.comartsandculture.google.com

-

Archaeology Magazine – “The World’s Oldest Writing” (May/June 2016)archaeology.orgarchaeology.org

-

World History Encyclopedia – Cuneiform (J. Mark, 2022)worldhistory.orgworldhistory.orgworldhistory.orgworldhistory.orgworldhistory.org

-

The Metropolitan Museum of Art – The Origins of Writing (I. Spar, 2004)metmuseum.orgmetmuseum.orgmetmuseum.orgmetmuseum.org

-

History.com – “9 Ancient Sumerian Inventions That Changed the World”history.comhistory.comhistory.com

-

World History Encyclopedia – Code of Ur-Nammu (J. Mark, 2021)worldhistory.org

-

History of Information – “The Earliest Known Egyptian Writing” (J. Norman)historyofinformation.comhistoryofinformation.com

-

World History Encyclopedia – Indus Script (C. Violatti, 2015)worldhistory.orgworldhistory.orgworldhistory.org

![Coin of Arsaces I. The reverse shows a seated archer carrying a bow, with the Greek legend reading "ΑΡΣΑΚΟΥ" (right) and "[AYT]OKPATOP[OΣ]" (left), meaning [coin of] "Arsaces"](https://historifyproduction.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/500px-Coin_of_Arsaces_I_1_Nisa-1-150x150.png)