The Founding of the Parthian Empire

The Parthian Empire, also known as the Arsacid Empire, was founded by Arsaces in 247 BCE and remained one of Western Asia’s most powerful states for nearly five centuries. The Parthians originated from the nomadic Dahae tribes of eastern Iran. Taking advantage of the declining Seleucid Empire, Arsaces declared independence in the region of Parthia and established the Arsacid dynasty, named after himself. This dynasty ruled for centuries, skillfully integrating various local cultures into a strong and resilient state.

The empire distinguished itself not only through its military and political achievements but also through its flexible administrative structure. By maintaining a delicate balance between central authority and local aristocracy, the Parthians managed to suppress internal unrest and govern a diverse population effectively. Their territory, initially limited to the Iranian plateau, gradually expanded to encompass Mesopotamia, Armenia, and parts of Afghanistan, forming a natural bridge between the eastern and western parts of the ancient world.

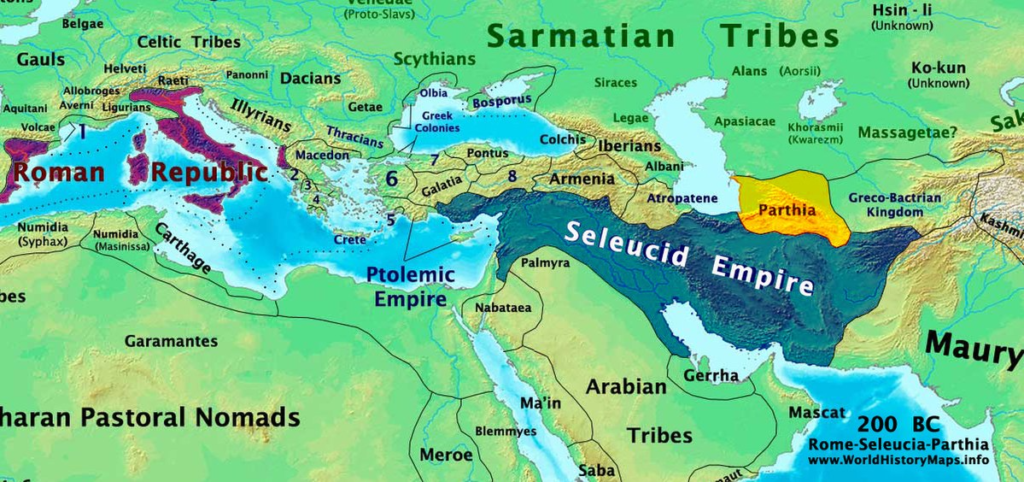

Original file by Ro4444, Map of the Parthian Empire under Mithridates II, CC BY-SA 4.0

The Parthian Empire was contemporaneous with the Roman Empire in the west and the Han dynasty in the east. It maintained a complex relationship with these powers, marked by both military conflicts and diplomatic exchanges. The Parthians demonstrated great skill in diplomacy and warfare, especially through their effective use of cavalry and hit-and-run tactics. One of their most famous victories occurred at the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BCE, where the Parthian army inflicted a devastating defeat on the Roman general Marcus Licinius Crassus. This victory solidified the Parthians’ reputation as a formidable force in the Western world.

Moreover, the Parthians controlled critical segments of the major trade routes between East and West, particularly the Silk Road. Through these routes, not only goods but also cultural ideas, religious beliefs, and technological innovations flowed. The Parthian Empire’s strategic location made it a vital player in the trade of silk, spices, and precious stones from China to the Mediterranean, positioning it as both a military and an economic powerhouse.

In the fields of art and architecture, the Parthians developed a distinctive cultural blend, merging Hellenistic influences with indigenous Iranian traditions. This synthesis was particularly evident in their sculpture, frescoes, and monumental tomb architecture. As a result, the Parthian Empire was not merely a political dominion but also a crossroads of civilizations, where different cultures met, interacted, and evolved.

Geography of the Parthian Empire

The Parthian Empire encompassed a vast and diverse geographic area that extended across the Iranian plateau, the fertile plains of Mesopotamia, the rugged highlands of Afghanistan, and the lush southern coasts of the Caspian Sea. This extensive territorial reach placed the Parthians at the crossroads of the ancient world, where cultures, economies, and military powers intersected.

At the heart of the empire lay the Iranian plateau, a region characterized by vast deserts, towering mountain ranges like the Zagros and Alborz, and fertile river valleys. This plateau served as the core of Parthian political and military power. It provided natural fortifications, making it difficult for external enemies to penetrate deep into Parthian territory. The Parthians skillfully adapted to these diverse landscapes, mastering both desert and mountain warfare, and using the terrain to their strategic advantage.

To the west, the Parthians controlled Mesopotamia, the historic land between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. This region was the economic lifeline of the empire, rich in agriculture and dotted with important cities such as Ctesiphon, which eventually became the imperial capital. Mesopotamia’s wealth and its location at the edge of the Roman world made it both a prize and a battleground, as Parthia and Rome repeatedly clashed over its control.

The silver drachma of Arsaces I

Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com, Coin of Arsaces I (1), Nisa mint, CC BY-SA 3.0

To the east, Parthian authority extended into Afghanistan and parts of modern-day Pakistan, reaching the ancient regions of Bactria and Arachosia. These eastern provinces were critical for maintaining the empire’s influence over Central Asian trade routes. They also served as cultural melting pots, where Greek, Persian, and Indian traditions blended following the legacy of Alexander the Great’s conquests.

Along the southern shores of the Caspian Sea, Parthia controlled the fertile and densely forested regions of Gorgan and Hyrcania. These areas were vital for both agriculture and military defense. Their location provided a buffer against nomadic invasions from the north, especially from Scythian and Sarmatian tribes.

The strategic geographic position of the Parthian Empire gave it unparalleled control over several critical trade arteries, most notably the Silk Road. By commanding key junctions and caravan routes, the Parthians acted as intermediaries between the East and the West. Goods such as silk, spices, gemstones, and precious metals moved through Parthian hands, enriching the empire and enhancing its diplomatic leverage with powerful neighbors like Rome and China.

This unique blend of diverse terrains — mountains, deserts, river valleys, and coastal plains — not only shaped the Parthian military and economy but also contributed to the empire’s rich cultural diversity. It allowed Parthia to serve as a vibrant meeting point where merchants, scholars, and emissaries from vastly different civilizations could interact, exchange ideas, and weave together the fabric of ancient global trade.

Parthia, shaded yellow, alongside the Seleucid Empire (blue) and the Roman Republic (purple) around 200 BC

Political Structure of the Parthian Empire

The Parthian Empire operated under a decentralized political system, a structure that set it apart from many other contemporary empires such as Rome or Han China. Unlike the centralized bureaucracies of its rivals, Parthian governance was built on a network of semi-autonomous local rulers who retained considerable power within their own territories while nominally recognizing the supremacy of the Parthian king.

At the apex of this system stood the King of Kings (Shahanshah), the supreme ruler from the Arsacid dynasty, who symbolized the unity and legitimacy of the empire. However, his authority was often more symbolic than absolute, as real power in many regions rested in the hands of powerful noble families. These aristocratic houses, such as the Surena, Karen, and Mihran clans, controlled vast tracts of land, commanded their own military forces, and administered their domains almost like independent kingdoms.

Each local ruler, often bearing the title of “king” or “satrap,” was responsible for managing the affairs of his own region. They collected taxes, enforced laws, maintained their own armies, and often minted their own coins bearing both the image of the Parthian monarch and their own local symbols. In return, they were expected to provide military support to the central authority when needed, particularly during external wars or major internal threats.

Drachma of Mithridates II Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com, Coin of Mithridates II of Parthia (obverse and reverse), Ray mint, CC BY-SA 3.0

This flexible political system had distinct advantages. By allowing local autonomy, the Parthians minimized rebellion among diverse ethnic and cultural groups spread across their vast territories. Local leaders had a vested interest in maintaining order within their regions, contributing to the empire’s overall stability for centuries. It also enabled rapid regional mobilization of forces without the need for a massive standing army controlled directly from the center.

However, decentralization came with significant risks. The Parthian kings often struggled to assert control over the powerful nobility, and internal rivalries among aristocratic families sometimes erupted into open conflict. Succession crises were common, as different noble houses supported competing claimants to the throne, leading to periods of civil war and fragmentation. The lack of a strong, centralized administrative system also made it difficult to coordinate large-scale economic projects or standardized governance across the empire.

Despite these challenges, the Parthian political model proved remarkably resilient. It reflected the empire’s deep-rooted respect for local traditions and regional diversity, and it allowed Parthia to govern an empire that stretched from the Euphrates to Central Asia for nearly five centuries. The balance between royal authority and noble autonomy became a defining characteristic of Parthian rule — a double-edged sword that both sustained and, at times, destabilized their imperial ambitions.

Royalty and Dynasties in the Parthian Empire

The Parthian Empire was ruled by the prestigious Arsacid dynasty, named after its founder Arsaces I, who established the foundation of Parthian rule in the mid-3rd century BCE. The Arsacid kings held a dual role, serving not only as political sovereigns but also as religious figures, embodying the sacred authority believed necessary to maintain order in the empire. This blend of spiritual and temporal power was a crucial element in legitimizing their rule over the culturally and ethnically diverse territories under their control.

The Arsacid monarchs carried the title of “King of Kings” (Shahanshah), a term that signified their supremacy over both the regional kings and satraps within the empire. Their religious role was often linked to traditional Iranian concepts of divine favor and royal charisma, drawing on ancient beliefs where kingship was seen as a mandate of the heavens. The king acted as a protector of the Zoroastrian faith, although the Parthians generally maintained a policy of religious tolerance, allowing a variety of cults and traditions to flourish across their vast dominion.

Han dynasty Chinese silk from Mawangdui, 2nd century BC. Silk from China was perhaps the most lucrative luxury item the Parthians traded at the western end of the Silk Road drs2biz, Silk from Mawangdui 2, CC BY-SA 2.0

Despite the grandeur associated with the throne, succession in the Parthian Empire was rarely smooth. Unlike more strictly hereditary systems, where primogeniture (inheritance by the firstborn son) was firmly established, Parthian succession was often contested. Powerful noble families and rival branches of the Arsacid dynasty frequently intervened in the royal succession, supporting different candidates for the throne based on their own interests. This lack of a clear, consistent rule of succession led to frequent periods of instability.

Civil wars and internal power struggles were a recurring feature of Parthian history. Upon the death of a king, it was not uncommon for multiple claimants to emerge, each backed by different factions of the nobility. In some cases, rival kings ruled simultaneously over different parts of the empire, further weakening central authority. These internal conflicts sometimes made the empire vulnerable to external threats, particularly from Rome, which often sought to exploit Parthian divisions to its advantage.

Nevertheless, the Arsacid dynasty demonstrated remarkable endurance. Despite internal discord, they managed to maintain their dynasty’s dominance for nearly five centuries, adapting to the ever-shifting political landscape. The Arsacids preserved a delicate balance between royal authority and noble autonomy, a testament to their political skill and the resilience of their imperial model.

The legacy of the Arsacid kings continued even after the fall of the Parthian Empire, influencing later Iranian dynasties such as the Sasanians, who inherited many aspects of Parthian court culture, political traditions, and concepts of kingship.

Military Strategies of the Parthian Empire

The Parthian Empire was renowned throughout the ancient world for its extraordinary military prowess and innovative battlefield tactics. In an era dominated by heavily armored infantry formations, the Parthians revolutionized warfare through their mastery of mobile cavalry warfare, making speed, flexibility, and precision their defining strengths. Their ability to adapt to various terrains and opponents gave them a crucial advantage against both eastern and western adversaries.

At the heart of the Parthian military system were the mounted archers, who formed the backbone of their armies. These highly skilled horsemen were capable of delivering devastating volleys of arrows while maintaining incredible mobility. Trained from a young age, Parthian cavalrymen could shoot accurately while riding at full speed, making them elusive and lethal opponents. Their constant motion frustrated enemy formations, especially the slow-moving heavy infantry of civilizations like Rome.

One of the Parthians’ most legendary battlefield maneuvers was the famous Parthian Shot. This tactic involved a mounted archer feigning a retreat, only to suddenly twist his torso while riding away and fire arrows back at the pursuing enemy. It was a devastating psychological and tactical move, often luring opponents into overextending their lines and falling into traps. The Parthian Shot became symbolic of Parthian cunning and adaptability and remains an iconic image of ancient warfare to this day.

A close-up view of the breastplate on the statue of Augustus of Prima Porta, showing a Parthian man returning to Augustus the legionary standards lost by Marcus Licinius Crassus at Carrhae

– Original by Andreas Wahra, new version by Till Niermann, Augustus Prima Porta (detail), CC BY-SA 3.0

In addition to their mounted archers, the Parthians made expert use of light cavalry tactics. Their forces emphasized speed, flexibility, and the ability to strike rapidly before melting away into the landscape. Light cavalry units conducted hit-and-run attacks, harassing enemy lines, cutting supply routes, and wearing down stronger but slower armies. These tactics allowed Parthian armies to win battles against numerically superior foes by avoiding direct confrontation and instead exploiting maneuverability and endurance.

The Parthian military also employed cataphracts — heavily armored cavalrymen equipped with long lances and protective armor for both horse and rider. In battle, the Parthians often combined waves of missile attacks from their light cavalry with sudden, crushing charges by their cataphracts. This dual approach could disorganize and shatter enemy formations, blending attrition with shock tactics in a highly effective manner.

Their mastery of cavalry warfare was famously demonstrated at the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BCE, where the Parthian general Surena annihilated a Roman force under Crassus. Using a combination of relentless arrow fire, feigned retreats, and cataphract charges, the Parthians inflicted one of the worst defeats in Roman history, cementing their reputation as unmatched masters of the battlefield.

Overall, the Parthian Empire’s military strategies reflected a profound understanding of mobility, terrain, and psychological warfare. Their emphasis on cavalry tactics not only made them dominant across the Iranian plateau and Mesopotamia but also forced neighboring powers like Rome to adapt and rethink their own military doctrines in response to the Parthian challenge.

The Parthian Empire Against Rome

The relationship between the Parthian Empire and Rome was marked by rivalry, diplomatic maneuvering, and frequent armed conflict. As two of the ancient world’s greatest powers, their clash was inevitable, especially over control of the fertile and strategically vital regions of Mesopotamia and Armenia. Among the numerous encounters between these empires, the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BCE stands out as a defining and symbolic moment in the long struggle between East and West.

The battle was precipitated by Roman ambitions to expand further eastward under the leadership of Marcus Licinius Crassus, a wealthy and influential Roman triumvir. Crassus sought personal glory and riches through a campaign against Parthia, underestimating both the difficulty of the terrain and the capabilities of the Parthian military. Confident of a quick and decisive victory, Crassus led a large Roman force into Mesopotamia without adequate preparation or reliable local alliances.

Waiting for him was Surena, one of the Parthian Empire’s most brilliant generals. Understanding the strength of the Roman heavy infantry and the weaknesses in their adaptability, Surena devised a plan that leveraged Parthia’s greatest advantages: mobility, endurance, and psychological warfare. His army was composed mainly of mounted archers and cataphracts — heavily armored cavalry — ideally suited to the open, arid plains where the battle took place.

Map of the troop movements during the first two years of the Roman–Parthian War of 58–63 AD over the Kingdom of Armenia, detailing the Roman offensive into Armenia and capture of the country by Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo

At Carrhae, the Parthians executed a masterclass in cavalry tactics. Mounted archers swarmed around the Roman formations, bombarding them with a relentless barrage of arrows, while remaining out of reach of the Roman infantry. Crassus’ soldiers, heavily burdened by their armor and rigid formations, were unable to effectively counter the fast-moving enemy. When the Romans attempted to charge, the Parthian cavalry feigned retreats, only to use the devastating Parthian Shot to inflict even greater casualties.

As Roman morale faltered and exhaustion set in, Parthian cataphracts launched crushing charges that shattered the Roman ranks. Crassus himself was killed during an ill-fated negotiation attempt after the battle, and the remnants of the Roman army were either slaughtered or captured. It is estimated that over 20,000 Roman soldiers died at Carrhae, with thousands more taken prisoner — a catastrophic loss for Rome and one of the worst defeats in its history.

The victory at Carrhae dramatically boosted the prestige of the Parthian Empire in the West. It demonstrated that the Roman legions, widely considered invincible, could be decisively defeated by a different style of warfare. The psychological impact was profound: Rome’s expansionist dreams in the East were tempered, and future Roman campaigns in the region would be marked by greater caution and respect for Parthian power.

Moreover, the success at Carrhae elevated Parthia’s status on the global stage, positioning it as a true counterbalance to Rome’s dominance. It also strengthened the internal prestige of the Arsacid dynasty and secured Surena’s place in history as one of antiquity’s most formidable generals.

Although later conflicts between Rome and Parthia would continue for centuries, the Battle of Carrhae remained a vivid symbol of Parthian strength — a moment when Eastern skill, patience, and innovation overcame Western brute force.

Trade and Economy of the Parthian Empire

The Parthian Empire owed much of its power and prosperity to its strategic location at the crossroads of major ancient trade routes, most notably the famed Silk Road. Situated between the civilizations of the East and West, the Parthians became essential intermediaries in the global exchange of goods, ideas, and cultures. Their control over these vital routes brought enormous wealth into the empire, strengthening its economy and enhancing its political influence far beyond its borders.

One of the most prized commodities that moved through Parthian territory was silk, originating in China. Highly coveted by Roman elites for its beauty and rarity, Chinese silk traveled westward along a series of caravan routes that passed through the steppes of Central Asia, the cities of Bactria, and the bustling trade hubs of Mesopotamia, all under Parthian supervision. By acting as middlemen, the Parthians profited immensely; they purchased silk and other luxury goods in the East and sold them at significantly higher prices to Roman merchants, enriching their economy without needing to produce these goods themselves.

Parthian king making an offering to the god Herakles–Verethragna. Masdjid-e Suleiman, Iran. 2nd–3rd century AD. Louvre Museum

But silk was only one of many treasures. The Parthian trade network also facilitated the movement of spices, gemstones, glassware, fine textiles, perfumes, artworks, and precious metals. In return, Roman products such as wine, olive oil, and fine ceramics made their way eastward, although Chinese and Central Asian markets often prized different types of goods. This vibrant trade turned Parthian cities into wealthy, cosmopolitan centers where diverse goods and cultures mingled.

The Parthian Empire thus served not only as a commercial bridge but also as a cultural bridge between the great civilizations of China, India, Persia, and Rome. Their cities became melting pots where Eastern and Western artistic styles, religious beliefs, and technological innovations interwove. This cultural fusion is particularly evident in Parthian art and architecture, where Greek, Persian, and Central Asian influences can be seen blending into unique forms.

Economic prosperity under the Parthians encouraged urban growth across their territory. Major cities like Ctesiphon, Seleucia, Hecatompylos, and Nisa flourished, becoming bustling centers of commerce, governance, and culture. These urban hubs boasted grand marketplaces, monumental public buildings, and elaborate gardens. With increased wealth came a flourishing of artistic expression: sculpture, coinage, pottery, and frescoes thrived, often reflecting a synthesis of Hellenistic and Iranian traditions.

Moreover, the steady flow of revenue from trade allowed the Parthian kings and noble families to finance large-scale construction projects and patronize the arts, further solidifying their social and political status. The economic success of the Parthian Empire played a crucial role in its ability to withstand external threats, manage internal divisions, and sustain a powerful military apparatus.

In sum, trade was not just a source of wealth for the Parthians; it was the lifeblood of their empire, linking them intricately to the broader currents of the ancient world and ensuring that their influence endured far beyond their own borders.

Cultural Legacy of the Parthian Empire

The Parthian Empire left a profound and lasting cultural legacy that reflected a rich fusion of diverse traditions. Situated at the intersection of East and West, the Parthians absorbed and reinterpreted a variety of cultural influences, blending Hellenistic styles inherited from the conquests of Alexander the Great with deep-rooted Iranian traditions. This cultural synthesis produced a distinctive Parthian identity that would influence later civilizations across the region.

In the realm of art, the Parthians developed a unique aesthetic that combined Greek realism with Persian symbolism. From the Greeks, they inherited techniques like naturalistic depiction and attention to human anatomy, yet they infused their artworks with a symbolic and often idealized quality drawn from Iranian spiritual and royal traditions. Parthian sculpture, for example, often portrayed figures with frontal poses and stylized features, emphasizing dignity and divine authority rather than dynamic movement. Wall paintings and reliefs from Parthian sites such as Dura-Europos demonstrate this distinctive stylistic blend, where vivid storytelling scenes are rendered with both expressive detail and formal grandeur.

Rock relief of Parthian king at Behistun, most likely Vologases III

Khoshamadgou, Parthian King Vologases at Behistun, CC BY-SA 4.0

Architecture under the Parthians also displayed a remarkable combination of innovation and tradition. Grand pillars, colonnades, and monumental iwans (large vaulted halls open on one side) became characteristic features of Parthian architectural design. Buildings often integrated complex and intricate decorative patterns, merging Mesopotamian, Persian, and Hellenistic elements. The city of Ctesiphon, later expanded by the Sasanians, featured massive arched halls that reflected Parthian engineering prowess and aesthetic ambition. Residential architecture also showcased sophistication, with houses arranged around central courtyards, adorned with elaborate stucco and fresco decorations.

Religiously, Zoroastrianism played a dominant role in the cultural landscape of the Parthian Empire. Although the Parthians were notably tolerant of different religious practices, Zoroastrian ideas about cosmic duality, divine kingship, and ritual purity deeply influenced state ideology and royal legitimacy. Fire temples, sacred to the Zoroastrian tradition, dotted the landscape, serving both religious and communal functions. However, the Parthian religious world was diverse: Greek deities, Mesopotamian gods, and later even early Christian communities found a place within the empire’s tolerant and pluralistic environment.

A Parthian (right) wearing a Phrygian cap, depicted as a prisoner of war in chains held by a Roman (left); Arch of Septimius Severus, Rome, 203 AD

Beyond religion and the arts, the Parthians made significant contributions to language and cultural transmission. They preserved and promoted Middle Iranian languages, such as Parthian Pahlavi, which later formed the linguistic foundation for Sasanian Persian. Their cultural flexibility helped sustain and spread Iranian traditions during a time when Hellenistic influence was strong throughout the Near East.

The cultural legacy of the Parthians did not end with the fall of their empire. Instead, many aspects of Parthian art, architecture, and religious thought were adopted and further developed by their successors, especially the Sasanian Empire. Through this continuation, Parthian contributions became woven into the broader tapestry of Iranian and Middle Eastern history, influencing the Islamic world centuries later.

In sum, the Parthian Empire was more than a military and political power — it was a cultural bridge that preserved ancient Iranian traditions, absorbed Hellenistic influences, and transmitted a rich, hybrid legacy to future generations.

Capitals of the Parthian Empire

The Parthian Empire was distinguished by its use of multiple capitals throughout its long history, reflecting the empire’s vast size, diverse population, and flexible approach to governance. Rather than having a single, fixed capital, the Parthians adapted to changing political, economic, and military circumstances by establishing major centers of power in key regions. Among these, Hecatompylos and Ctesiphon stand out as the most prominent.

One of the early capitals of the Parthian Empire was Hecatompylos, meaning “City of a Hundred Gates,” located near modern-day Damghan in Iran. Strategically positioned on important trade routes crossing the Iranian plateau, Hecatompylos served as a vital administrative and military hub during the formative years of the Parthian state. The city’s prominence reflected the Parthians’ eastern Iranian origins and their initial focus on consolidating control over the Iranian heartland. Although not much of Hecatompylos survives today, ancient sources describe it as a thriving, cosmopolitan center during the early Arsacid period.

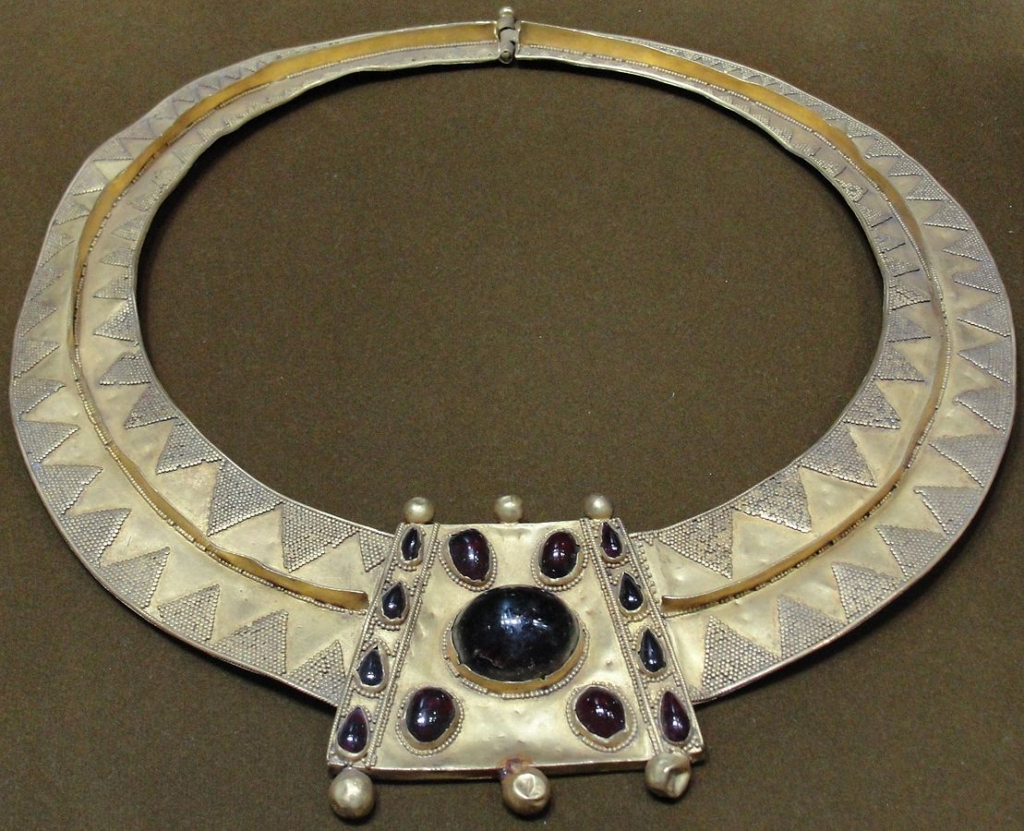

Parthian golden necklace, 2nd century AD TruthBeethoven, Golden Necklace – Parthian Empire 2nd AD, CC BY-SA 3.0

As the Parthian Empire expanded westward, particularly into Mesopotamia, a new and far more significant capital emerged: Ctesiphon. Situated on the eastern bank of the Tigris River, near modern-day Baghdad, Ctesiphon grew into the political and cultural heart of the Parthian Empire. Thanks to its location at the crossroads of trade routes linking Iran, Mesopotamia, and the Mediterranean, the city prospered immensely. Over time, Ctesiphon became not only the most famous Parthian capital but also one of the largest and richest cities in ancient Mesopotamia.

Ctesiphon functioned as the primary residence of the Parthian kings and a vibrant center of commerce, diplomacy, and culture. The city featured grand palaces, extensive gardens, bustling marketplaces, and monumental architecture, much of which would later influence the urban planning and architecture of the succeeding Sasanian dynasty. Its proximity to the Roman frontier also made it a focal point of military strategy; it was frequently contested in Roman-Parthian wars, with Roman emperors such as Trajan and Septimius Severus launching major campaigns to capture it.

In addition to Hecatompylos and Ctesiphon, other important cities like Seleucia on the opposite bank of the Tigris, and Ecbatana (modern Hamadan), served as seasonal or secondary capitals, particularly during periods of royal movement. This network of cities provided the Parthian rulers with flexibility, allowing them to govern a sprawling and diverse empire more effectively.

Ultimately, the capitals of the Parthian Empire, especially Ctesiphon, symbolized the wealth, multicultural nature, and strategic savvy of Parthian rule. They stood as dynamic centers where Iranian, Mesopotamian, and Hellenistic traditions met and flourished, leaving an enduring mark on the history of the ancient Near East.

The Weakening of the Parthian Empire

Despite its centuries of dominance, the Parthian Empire eventually began to weaken under the weight of internal and external pressures. Its decentralized political structure, once a source of flexibility and stability, gradually became a vulnerability as the empire faced increasing challenges both from within and without.

One of the primary factors contributing to the empire’s decline was the prevalence of civil wars and succession disputes. The lack of a clear and consistent system of succession often led to fierce competition among members of the Arsacid dynasty and powerful noble families. Rival claimants to the throne frequently gathered their own military forces, plunging the empire into periods of civil strife. These internal conflicts drained resources, weakened military readiness, and eroded public confidence in the central government.

At the same time, the Parthians faced constant external pressure from Rome, their powerful and persistent western rival. Although the Parthians had secured impressive victories, such as the Battle of Carrhae, they were never able to fully neutralize Roman ambitions in the East. Repeated Roman invasions, often exploiting Parthian internal divisions, inflicted heavy losses and destabilized the western provinces. Roman campaigns under emperors like Trajan and Septimius Severus struck deep into Parthian territory, capturing key cities like Ctesiphon, albeit temporarily. These repeated incursions not only devastated local economies but also undermined the prestige of the Arsacid kings.

A Parthian ceramic oil lamp, Khuzestan Province, Iran, National Museum of Iran

Fabienkhan, Iran-bastan-32, CC BY-SA 2.5

Meanwhile, the growing power of regional nobles further destabilized the empire. As local aristocratic families amassed wealth and military power, they became increasingly independent, often acting as sovereign rulers within their domains. The central authority struggled to exert effective control over these semi-autonomous regions. In some cases, powerful noble houses withheld military support or even backed rival claimants during succession crises, exacerbating political fragmentation.

The empire’s decentralized nature, once suited to governing a vast and diverse territory, thus became a liability. Without a strong, unified administrative system, the Parthian kings found it difficult to mobilize resources efficiently, enforce loyalty, or launch coordinated military campaigns. The erosion of royal authority weakened the state’s ability to respond effectively to both internal rebellions and external threats.

By the early 3rd century CE, these cumulative weaknesses left the Parthian Empire vulnerable to new challengers. The rise of the Sasanian dynasty, spearheaded by Ardashir I, capitalized on the Parthians’ internal chaos. In a series of decisive battles, Ardashir defeated the last Arsacid ruler, Artabanus IV, bringing an end to the Parthian Empire and establishing the Sasanian Empire, which would go on to restore centralized authority and usher in a new era of Iranian greatness.

In the end, the fall of the Parthian Empire was not the result of a single catastrophe but rather the culmination of long-standing internal weaknesses, exacerbated by relentless external pressures and the gradual disintegration of centralized royal power.

The Fall of the Parthian Empire

The fall of the Parthian Empire in the early 3rd century CE marked the end of one of the ancient world’s longest-lasting and most influential powers. After centuries of rule, the Arsacid dynasty succumbed to a combination of internal weaknesses and the rise of a new, ambitious force within Persia itself.

At the forefront of this transformation was Ardashir I, a Persian noble from the province of Persis (modern-day Fars, in southern Iran). Originally a local ruler under nominal Parthian authority, Ardashir capitalized on the growing disunity within the empire. Through a series of successful military campaigns, he consolidated power in the south and began openly challenging Arsacid supremacy. His movement found support among those who longed for a return to a strong, centralized monarchy rooted in ancient Persian traditions.

The decisive confrontation came in 224 AD, at the Battle of Hormozdgan, where Ardashir’s forces clashed with those of the last Parthian king, Artabanus IV. In a fierce battle, Ardashir emerged victorious, killing Artabanus IV and effectively ending the Parthian Empire. Following his victory, Ardashir crowned himself Shahanshah (“King of Kings”) and founded the Sasanian Dynasty, which would rule Persia for the next four centuries and restore much of the imperial grandeur that had characterized earlier Iranian empires like the Achaemenids.

Parthian cataphract fighting a lion

Despite the fall of their political structure, the legacy of the Parthians endured in many significant ways. Their influence on art, warfare, and culture continued to shape Iranian civilization long after the Arsacid dynasty had vanished. Sasanian art, for example, carried forward many Parthian aesthetic traditions, such as the frontal pose in sculpture and monumental palace architecture. In warfare, the use of heavy cavalry (cataphracts) — perfected by the Parthians — became a standard feature of Sasanian military tactics and later influenced Byzantine and Islamic armies.

Culturally, the Parthians had acted as a bridge between East and West, and this role was inherited and expanded upon by the Sasanians. Elements of Parthian governance, regional autonomy, and religious policies found echoes in early Sasanian administration, even as the Sasanians moved toward greater centralization.

In essence, while the Parthian Empire came to an end on the battlefield, its spirit and innovations lived on, profoundly impacting not only their immediate successors but also the broader historical and cultural development of the Middle East and Central Asia for centuries to come.

![Coin of Arsaces I. The reverse shows a seated archer carrying a bow, with the Greek legend reading "ΑΡΣΑΚΟΥ" (right) and "[AYT]OKPATOP[OΣ]" (left), meaning [coin of] "Arsaces"](https://historifyproduction.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/500px-Coin_of_Arsaces_I_1_Nisa-1-150x150.png)